Conductivity and Control:

Graphene in the Evolution of Antistatic Materials

In the early 18th century, scientists began to notice that some materials, when rubbed together, were mysteriously attracted to one another, while others—especially those of different natures—were consistently repelled. After many observations of the same phenomenon, researchers concluded that invisible fluids or charges were being transferred between certain objects, later described as attractive or repulsive forces.

It was Benjamin Franklin who proposed that only one type of fluid was exchanged between objects, and that differing charges resulted from an excess or deficiency of this fluid. Franklin tested this with wax and wool, observing that rubbing them caused the wool to extract the invisible fluid from the wax—leading to a surplus in the wool and a deficit in the wax. This imbalance would then generate attractive forces as the system sought to restore equilibrium.

“It was later discovered that this invisible ‘fluid’ was made up of tiny fragments of matter called electrons— the smallest known carriers of electric charge.”

Today, we understand that electric charge results from the transfer of electrons between bodies that generate electrostatic tension. However, in insulating materials like plastics, the charge remains static and localized at the point of contact. When such plastics encounter objects at different potentials—such as a person or an electronic microcircuit—static electricity may discharge via a spark or arc. This can damage electronic equipment or even trigger fires and explosions, especially in the presence of flammable substances. For this reason, the use of antistatic materials in construction products, electronics, storage centers, textiles, and many other applications is critical.

“Static charge is also known as static electricity or electrostatics.”

Plastics are found in nearly every environment. While they serve countless purposes, the static charge they accumulate can limit their use. This is why antistatic additives are often incorporated to reduce electrical resistance, making them suitable for producing antistatic packaging for electronics, automotive, or chemical industries. These materials may be biodegradable biopolymers like polylactic acid (PLA) and cellulose acetate (CA) or non-biodegradable petrochemical plastics such as polyethylene (PE), polypropylene (PP), and polyethylene terephthalate (PET). Antistatic solutions are also used in construction supplies made from PVC or rubber, especially in chemical plants, gas stations, or coal mines.

How many types of antistatic additives are there?

The family of antistatic additives is broad. They include ionic, non-ionic, conductive polymers, phosphorus-based additives, and carbon-based materials. In this article, we focus on the latter—specifically, carbon black, graphite, and most notably, graphene.

“According to ASTM D257-78, the surface resistivity of antistatic materials ranges from 1.0×10⁵ to 1.0×10¹² Ω/sq.”

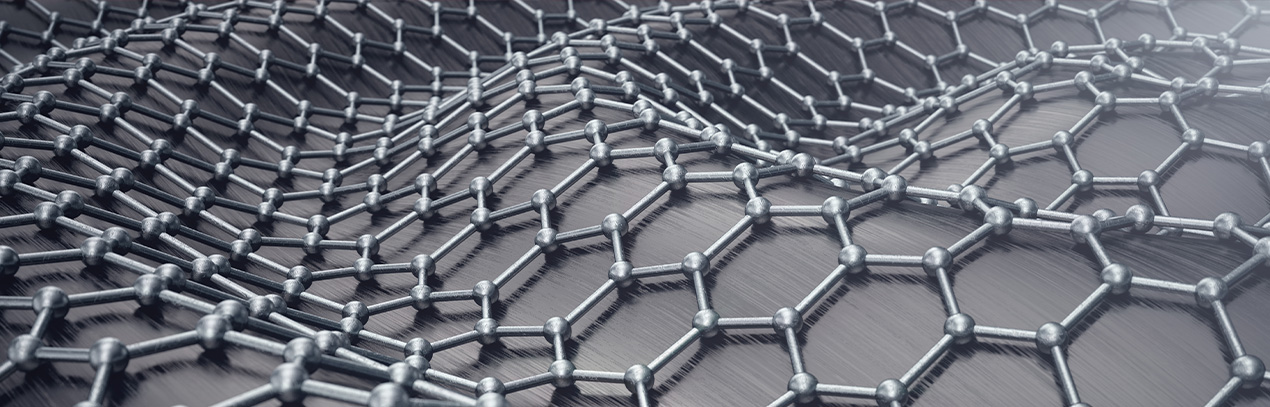

Graphene is a carbon nanostructure with exceptional electrical conductivity (0.96 × 10⁸ Ω·m⁻¹), making it a powerful antistatic agent. Unlike graphite—a 3D carbon structure made of millions of graphene layers—and carbon black, which is amorphous and tends to form large aggregates, graphene has a well-organized sheet-like structure with a high surface area accessible on both sides. This allows it to interact intimately with other molecules and modify the properties of many materials, particularly polymers—not only by reducing static, but also by enhancing mechanical strength, thermal resistance, and barrier properties.

Technically, graphene is composed solely of carbon atoms. But in practice, there are as many types of graphene as there are production methods—whether producing pristine graphene, graphene oxide (GO), or reduced graphene oxide (rGO)—each potentially functionalized during or after production. These functionalizations are often necessary to improve graphene’s interaction with specific polymer matrices and to impart desired properties, such as antistatic behavior.

To integrate graphene into PLA used in antistatic packaging, plasticizers like thymol, polyethylene glycol (PEG), or dibutyl sebacate (DBS) can serve as carriers—not just to reduce resistivity but also to enhance mechanical strength and barrier properties. Literature reports show that graphene in PLA can increase electrical conductivity from 1.39E-12 S/cm to 2.83E-4 S/cm. For antistatic rubber flooring, graphene can be functionalized with zinc methacrylate to reduce resistivity by up to three orders of magnitude.

Another critical factor is graphene’s proper dispersion and integration into the host matrix—something that varies depending on the material. For rubber, graphene can be functionalized with 3-glycidyloxypropyltrimethoxysilane, a coupling agent that bonds organic and inorganic materials. For PET, GO can be functionalized with p-phenylenediamine (PPD), which improves dispersion, thermal stability, and boosts antistatic performance by up to eight orders of magnitude.

In the case of cellulose acetate (CA), a biodegradable polymer gaining popularity in packaging, direct functionalization of graphene with CA molecules during synthesis improves both dispersion and static dissipation—lowering surface resistivity from 1.09×10¹² Ω/sq to 1.51×10⁹ Ω/sq. A similar strategy applies to PVC, using dioctyl phthalate (DOP), a plasticizer that can assist during graphite exfoliation to create a graphene more compatible with PVC and reduce resistivity from 10¹⁶ Ω-cm to 2.5 × 10⁶ Ω/sq.

Clearly, graphene represents a technological leap forward in the development of advanced plastics. Its capacity as an effective antistatic additive—along with its multifunctional benefits—makes it a key material for driving innovation in this field. However, its performance depends heavily on selecting the right type of graphene, the functionalization process, and its integration into the polymer matrix. As research continues, graphene is becoming an increasingly vital solution for meeting the safety, performance, and sustainability demands of the plastics industry.

Written by: EF/DHS

References

- aif M. Jaseem and Nadia A. Ali. Antistatic packaging of plasticized biodegradable polylactic acid /graphene nancomposites. Pak. J. Biotechnol. Vol. 16 (2) 81-90 (2019)

- Josiani Aparecida da Silva, et al., The combined effect of plasticizers and graphene on properties of poly(lactic acid), Inc. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2018, 135, 46745.

- Saif M. Jaseem and Nadia A. Ali Antistatic packaging of carbon black on plastizers biodegradable polylactic acid nanocomposites 2019 J. Phys.: Conf. Ser. 1279 012046

- Zhaorui Meng, et al., Grafting macromolecular chains on the surface of graphene oxide through crosslinker for antistatic and thermally stable polyethylene terephthalate nanocomposites. 2022, RSC Advances, 12, 52, 33329.

- Zijun Gao et al., Graphene nanoplatelet/cellulose acetate flm with enhanced antistatic, thermal dissipative and mechanical properties for packaging, Cellulose (2023) 30:4499

- Zi-Bo Wei, et. al., Antistatic PVC-graphene Composite through Plasticizer-mediatedExfoliation of Graphite, chinese J. Polym. Sci. 2018, 36, 1361